Conceptual Fallacies and How to Avoid Them

Logical fallacies are not the only errors that retard thinking. Conceptual fallacies do, too, and often in subtler, more destructive ways.

Just as logical fallacies violate principles of logic, conceptual fallacies violate those of concept-formation.

The basic principles of concept-formation are presented in Ayn Rand’s Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology (ITOE), which I highly recommend. Fallacies that violate these principles include package-deals, anti-concepts, frozen abstractions, floating abstractions, and stolen concepts. Below are definitions and examples of each, along with brief indications of the principles they violate.

This is not an exhaustive presentation of conceptual fallacies (that would require a book); rather, it’s a primer, showing their general nature, how to spot and avoid them in your thinking, and how to address them when others commit them.1

Also, this is a living document, which I’ll refine and expand over time. I welcome your suggestions for improvement.

Package-Dealing: Mentally Mixing the Logically Unmixable

A concept is a mental integration of two or more units possessing the same distinguishing characteristic(s), with their particular measurements omitted.2

The purpose of a concept is to mentally unite essentially similar things (e.g., dogs) and to distinguish them from essentially different things (e.g., cats) so that when we use the corresponding word, we know what we are thinking or talking about. Properly formed (and defined), a concept draws a mental bright line between the things to be included in a classification and those to be excluded from it—between the things the concept refers to and those it doesn’t. Package-deals violate this principle.

The fallacy of package-dealing consists in conceptually combining things that are superficially similar but essentially different and, thus, logically do not belong under the same concept.3 If and when we commit this fallacy, we muddle our thinking about the subject in question and make clear communication impossible.

Package-dealing is similar to the logical fallacy of equivocation, but it operates on a different scale. Whereas equivocation consists in using a word or phrase in multiple senses within the same argument, package-dealing consists in packaging two or more essentially different ideas into a single word or phrase and thereby treating essentially different things as though they are essentially the same.

Note that the use of these terms is not inherently fallacious. Rather, the fallacy consists in using a given term in a way that groups together, into a single mental package, things that are essentially different and thus do not belong together under the same concept. Let’s look at some examples.

Democracy

An extremely common instance of package-dealing is the mental blending of “majority rule” and “rights-protecting social system” under the term “democracy.”

If the majority dictates the laws of a society or what people may and may not do, the society is not a rights-protecting society but a dictatorship of the majority—which can vote to do whatever it pleases. In the democracy of ancient Athens, for instance, the majority voted to put Socrates to death for speaking his mind and asking vexing questions. Needless to say, democracy did not protect his rights. And many people today—perhaps the majority in some countries and states—would love such power to silence those who express views they dislike.

A democracy is essentially different from a rights-protecting social system, which is why the American founders opposed democracy and created instead a constitutional republic, the purpose of which was to protect individual rights regardless of majority (or minority) opinions or desires. Observe that the term “democracy” is nowhere to be found in the Declaration of Independence or the U.S. Constitution. Indeed, the Constitution, with its separation of powers, system of checks and balances, and Bill of Rights, is designed precisely to prohibit majority rule.

The U.S. system involves a democratic process, in which citizens vote to elect their political representatives. But this does not make it a democracy or constitute majority rule. It simply means that the U.S. republic entails a process by which citizens elect their representatives.

In a fully rights-protecting constitutional republic (which has yet to exist), the constitution would limit the government to the protection of individual rights, require it to protect individual rights fully and consistently, and forbid it ever to violate individual rights—regardless of any democratic consensus to the contrary. In a full-fledged democracy, by contrast, the government would do whatever the majority at any given time voted for it to do.

If we want to think and communicate clearly about politics, individual rights, democracy, and the like, we need a clear understanding of the relevant terms. “Democracy” means majority rule. “Democratic process” means voting is involved. And “rights-protecting republic” refers to a social system that recognizes and protects individual rights.

Equality

The word “equality” is a major part of today’s political conversations and debates. But when someone uses the term, what exactly does he mean? For instance, if a politician says, “I stand for equality” or “I will work to ensure equality for all,” what is he talking about? Without further context, we might take him to mean any of the following:

- Equality of outcome or wealth: a condition in which everyone has the same amount of wealth or spending power regardless of what he has or hasn’t produced.

- Equality of opportunity: a condition in which everyone has the same opportunities—for example, to attend Harvard, to perform in Carnegie Hall, to purchase a mansion, to vacation in Fiji, or to compete in women’s sports.

- Equality before the law: a condition in which everyone is treated equally by the government and legal system—so, if a law applies to one person, it applies to all; if a law protects one person’s rights, it protects everyone’s rights; and if a law enslaves one person, it enslaves all others, too.

- Equality of full freedom to act in accordance with one’s own judgment and to keep and use the product of one’s effort: the only condition in which all individuals can live fully as human beings rather than partially as involuntary servants. (This is the condition established by capitalism—more on that below.)

These meanings of “equality” share a superficial similarity—each pertains to equality of something or of some sort. But, in each case, the “something” or “some sort” is essentially different. Thus, if we want to think and communicate clearly, we must keep these essentially different things separate and distinct in our minds. Put negatively, we must not package these essentially different things into a single concept—“equality”—and thus treat them as though they are essentially the same. To do so is to commit the fallacy of package-dealing and to retard our ability to think or communicate clearly about the issue at hand.

How should we use the term “equality”? By stating clearly what we mean by it in any context in which we use it—and by asking others to do so, too. Such clarity is good for everyone who wants to maintain cognitive contact with reality.4

Power

Power is a package-deal when used to equate “economic power” with “political power.” As Rand elaborated:

You have heard it expressed in such bromides as: “A hungry man is not free,” or “It makes no difference to a worker whether he takes orders from a businessman or from a bureaucrat.” Most people accept these equivocations—and yet they know that the poorest laborer in America is freer and more secure than the richest commissar in Soviet Russia. What is the basic, the essential, the crucial principle that differentiates freedom from slavery? It is the principle of voluntary action versus physical coercion or compulsion.

The difference between political power and any other kind of social “power,” between a government and any private organization, is the fact that a government holds a legal monopoly on the use of physical force. . . .

No individual or private group or private organization has the legal power to initiate the use of physical force against other individuals or groups and to compel them to act against their own voluntary choice. Only a government holds that power. The nature of governmental action is: coercive action. The nature of political power is: the power to force obedience under threat of physical injury—the threat of property expropriation, imprisonment, or death.5

Whereas political power is that of force or coercion, economic power is that of production or trade. To the extent that a person (or business) produces goods or services that others are willing to buy (e.g., cookies, software, swim lessons), he has economic power—power to trade the product of his effort for goods or services produced by others (money being a medium of exchange).

Political power and economic power have a superficial similarity—both involve the capacity to cause change in human conditions. But they are essentially different. If we want to think clearly about politics and economics, we must keep these essentially different things separate and distinct in our minds.6

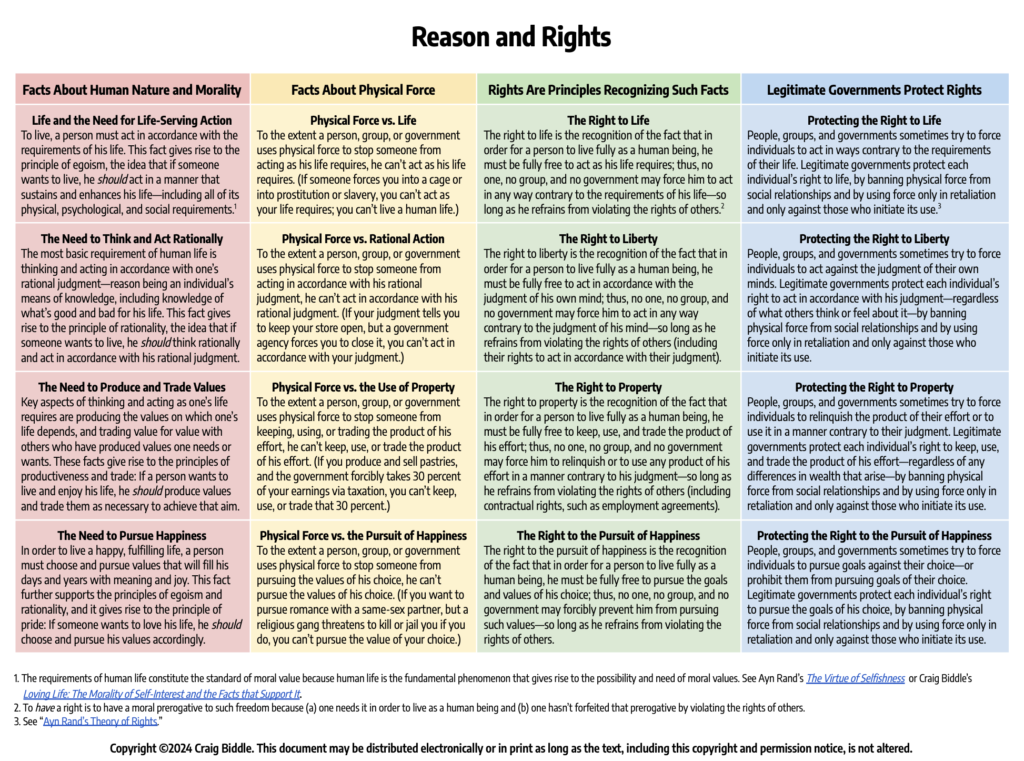

Rights

“Rights” is a package-deal when used to conflate “a moral prerogative to be free from coercion” with “a moral prerogative to be provided with goods or services.” These are not the same thing. Indeed, they are mutually exclusive.

The notion that a person has a moral prerogative or a right to be given goods or services—such as a job, a “living wage,” an education, or health care—implies that someone must be forced to provide him with such goods. The right to freedom from physical force is not the same thing as an alleged “right” to force people (or have the government force them) to provide you (or others) with goods or services.

There is no right to violate a right. As Rand put it, “There can be no such thing as ‘the right to enslave.’”7

Capitalism

“Capitalism” is a package-deal when used to combine “the social system in which government fully recognizes and protects individual rights, including property rights,” with “a social system in which government violates individual rights to some extent by coercing people or businesses, or forcibly redistributing wealth.” These are not the same thing. The first is capitalism; the second is some kind and degree of statism—whether a mixed economy, a welfare state, or some more-consistent form of statism, such as socialism, communism, or theocracy.

All of politics is about freedom versus force. It’s about when, under what circumstances, and to what extent government may use force against people.

Capitalism (an ideal yet to be achieved) is the social system in which government bans the use of physical force from social relationships and uses force only in retaliation—and only against those who initiate its use. Thus, capitalism fully protects the rights of all individuals and businesses (which are made up of individuals), leaving everyone fully free to act in accordance with his own judgment, so long as he doesn’t initiate force against others (i.e., violate rights).

All other social systems permit government to initiate physical force against people and businesses to some extent for some alleged “greater good”—whether “society” (socialism), “the community” (communism), “the group” (fascism), “God” (theocracy), “the poor” (welfare statism), “people with political pull” (cronyism), or anything else treated as morally and politically superior to the rights of the individual.

Because capitalism protects rights fully, and mixed economies and welfare states violate rights to some extent, we need to keep these essentially different things separate and distinct in our minds. To use the term capitalism in a way that packages together “rights-protecting system” with “rights-violating system” is to mentally mix the logically unmixable. It is to retard one’s thinking and one’s ability to communicate clearly about politics, capitalism, mixed economies, and other social systems.

If we want to think and communicate clearly about such matters, we must call capitalism “capitalism,” a mixed economy “a mixed economy,” cronyism “cronyism,” and statism “statism.” And when we need to specify a particular kind of extreme statism, we should use the terms that do so, such as “socialism,” “communism,” or “theocracy.”

Such clarity always works to the advantage of those who want to protect individual rights and political freedom.8 Among other ways, it stops politicians, pundits, and regressives from getting away with the lie that “capitalism has failed”—when what has failed is the mixed economy, which is shot through with coercive regulations, cronyism, and other elements of statism.

Secularism

“Secularism” is a package-deal when used to combine “a naturalistic (rather than a supernaturalistic) approach to understanding the world and human needs” with “moral subjectivism” or “cultural relativism.” These are not the same thing. Yet religious conservatives often conflate these essentially different things under the term “secularism.” This conflation lends credence to a dangerous and widely accepted false alternative: Either morality comes from supernatural commandments and is thus “objective,” or morality is made up by people and is therefore “subjective.” (“If there is no God, anything goes.”) This package-deal and false alternative blind people to the possibility of a secular, objective morality—such as Rand’s Objectivist ethics or rational egoism. And when blinded to that, people are also blinded to the possibility of a secular, objective foundation for individual rights and political freedom—because the objective grounding for these lies precisely in rational egoism and, by extension, the objective grounding for it.

If we want to think clearly about the world, our needs, morality, individual rights, and freedom, we need to keep the concept of “secularism” and those of “moral subjectivism” and “cultural relativism” separate and distinct in our minds.9

(It’s worth noting here that religion, ironically, is one of the main sources and causes of moral subjectivism. According to religion, if God says something is true or right or good, then it is—because He said so. That is subjectivism, albeit “supernatural subjectivism.” It’s the idea that something is good or bad because some supernatural consciousness said so. Further, to accept that God’s say-so is the standard of truth and morality, you must accept the say-so of religious people who say that it is. “God exists, and His word is the truth.” How does a religious person know this? He “knows” it because he said so—or, as he will put it, “because I have faith,” which means “because I want to accept ideas in support of which there is no evidence.” And he expects you to accept it based on feelings, too—otherwise he would present evidence.)10

Tolerance (or Toleration)

“Tolerance” is a package-deal when used to combine “respect for individual rights” with “refusal to judge the moral status of people’s choices, ideas, or actions.” These are not the same thing, and they logically don’t belong under the same concept.

“Respecting rights” means refraining from initiating physical force against people. It means leaving them free to act on their own judgment for their own purposes—so long as they don’t initiate force against others and thus stop them from acting on their own judgment. “Refusing to judge the moral status of people’s choices, ideas, or actions” means refusing to evaluate a huge category of things that have a significant impact on your life—things that could either help you to succeed in life and achieve happiness, or throttle or thwart your efforts to survive and thrive. Refusing to judge a friend’s act of dishonesty, such as cheating on a test or stealing from a store, makes you morally complicit in the act, compromises your integrity, causes feelings of guilt, and extends your friendship with someone who is willing to be dishonest—which can lead to all sorts of additional problems. Refusing to judge the injustice of men competing in women’s sports enables these unjust men to continue robbing women of their rightful earnings. Refusing to judge the evil of someone advocating socialism—in full view of its anti-individualism and its blood-soaked history—condones his evasions and encourages him to continue advocating this murderous monstrosity.

As Rand writes:

Nothing can corrupt and disintegrate a culture or a man’s character as thoroughly as does the precept of moral agnosticism, the idea that one must never pass moral judgment on others, that one must be morally tolerant of anything, that the good consists of never distinguishing good from evil.

It is obvious who profits and who loses by such a precept. It is not justice or equal treatment that you grant to men when you abstain equally from praising men’s virtues and from condemning men’s vices. When your impartial attitude declares, in effect, that neither the good nor the evil may expect anything from you—whom do you betray and whom do you encourage? . . .

The precept: “Judge not, that ye be not judged” . . . is an abdication of moral responsibility. . . . The moral principle to adopt in this issue, is: “Judge, and be prepared to be judged.”11

We can and do morally judge people while respecting their rights. For instance, I judge people who treat faith as a means of knowledge as dishonest for doing so. I judge them negatively for pretending that just believing something to be true makes it true. But I also respect their right to treat faith as a means of knowledge—providing they don’t act on religious beliefs that call for rights violations, such as killing homosexuals, flying passenger jets into skyscrapers, or de-clitorizing girls.

“Respecting rights” and “refusing to morally judge people” are categorically different things. We should not use the word “tolerance” (or “toleration”) in a way that treats them as though they are the same.12

Sacrifice

“Sacrifice” is a package deal when used to mentally mix “giving up a greater value for the sake of a lesser value”—with “giving up a lesser value for the sake of a greater value.” These actions have a superficial similarity, in that both involve giving up a value. But they are essentially different in that one results in a net loss, and the other results in a net gain.

If you have a big presentation tomorrow that is more important to your life than a night at a club with your friends, and if you stay home tonight, prepare for the presentation, and ace it, you achieve a net gain. If instead you go to the club with your friends and botch the presentation, you incur a net loss. This is a black-and-white difference.

Likewise, writes Rand:

If a man who is passionately in love with his wife spends a fortune to cure her of a dangerous illness, it would be absurd to claim that he does it as a “sacrifice” for her sake, not his own, and that it makes no difference to him, personally and selfishly, whether she lives or dies.

Any action that a man undertakes for the benefit of those he loves is not a sacrifice if, in the hierarchy of his values, in the total context of the choices open to him, it achieves that which is of greatest personal (and rational) importance to him. In the above example, his wife’s survival is of greater value to the husband than anything else that his money could buy, it is of greatest importance to his own happiness and, therefore, his action is not a sacrifice.

But suppose he let her die in order to spend his money on saving the lives of ten other women, none of whom meant anything to him—as the ethics of altruism would require. That would be a sacrifice. . . . What distinguishes the wife from the ten others? Nothing but her value to the husband who has to make the choice—nothing but the fact that his happiness requires her survival.13

Sacrificial actions and non-sacrificial actions are opposite kinds of actions. Thus, we need different concepts—and correspondingly different words and definitions—for these essentially different things. The surrender of a greater value for the sake of a lesser value is properly called a “sacrifice” because it results in a net loss. The exchange of a lesser value for the sake of a greater value is properly called a “trade,” a “profit,” an “investment” (or the like) because it results in a net gain.

If we want to know what we are thinking and talking about when we use the term “sacrifice,” we must keep these essentially different kinds of actions separate and distinct in our minds.14

Altruism

“Altruism” is a package-deal when used to combine the notion that being moral consists in “living for others” or “self-sacrificially serving others” with the idea that being moral involves “having good will toward others” or “serving people in win-win or non-sacrificial ways.” These ideas are superficially similar—each makes a claim about the manner in which people should treat or serve others. But they are essentially different in that living for others or serving people in a self-sacrificial way is fundamentally different from treating people with goodwill or serving them in non-sacrificial ways.

Consider Mother Teresa and J. K. Rowling. Both women have “served” people. But this similarity is superficial. The way in which they served people is fundamentally different: Mother Teresa “served” people by exchanging her time and effort for nothing; for instance, she washed the feet of strangers for no compensation whatsoever. Rowling, by contrast, served people (and continues doing so) by trading value for value to mutual advantage—an exchange in which both sides gain. For instance, she wrote the Harry Potter series and sold the books to millions of people, making herself rich and bringing great joy to countless readers (and moviegoers). Mother Teresa is correctly regarded as an altruist. J. K. Rowling is not.

Likewise, if you forgo a trip to the beach with your friends in order to do community service from which you receive no personal benefit, that is altruistic. If instead you forgo the selfless community service and go to the beach with your friends because you want to live happily and enjoy your life, that is not altruistic, but egoistic—an act of self-interest. And if you forgo both of those alternatives to stay home to care for your beloved cat who is ill, that too is egoistic—it’s acting non-sacrificially: with respect to your hierarchy of values.

Altruism is the morality of self-sacrifice and personal loss; it does not condone self-interest or personal gain. As philosopher Thomas Nagel explains, altruism entails “a willingness to act in consideration of the interests of other persons, without the need of ulterior motives”—“ulterior motives” meaning personal interests or personal gains.15 “To the extent that [people] are motivated by the prospect of obtaining a reward,” explains philosopher Peter Singer, “they are not acting altruistically.”16

Engaging with people in win-win or non-sacrificial ways is fundamentally different from engaging with them in win-lose or self-sacrificial ways. To package these essentially different ways of acting under the same term—“altruism”—is to create a package-deal that retards one’s thinking.

If we want to think and communicate clearly about the nature and meaning of morality, altruism, self-interest, and the like, we must keep these essentially different ways of engaging with people clear and distinct in our minds.17

Selfishness

“Selfishness” (or “selfish”) is a package-deal when used to conflate “choosing and pursuing goals that advance one’s interests given the full context of one’s knowledge and other people’s rights” and “choosing and pursuing goals without regard to the full context of one’s knowledge and other people’s rights.”

It makes no sense to combine the choices and actions of producers and traders (e.g., Jeff Bezos and Taylor Swift) with those of parasites and thieves (e.g., Elizabeth Holmes and Sam Bankman-Fried) and treat them as though they are essentially the same. Although their behaviors involve a superficial similarity—choosing and pursuing goals—they also involve a glaring and fundamental difference: One set of behaviors involves choosing and pursuing goals rationally, in a productive, rights-respecting way; the other set involves choosing and pursuing goals irrationally, in a parasitic or rights-violating way. One of these categories of choices and actions leads to a lifetime of success and happiness; the other leads to feelings of guilt, unhappiness, and the likelihood of imprisonment and premature death (e.g., Bernie Madoff and Jeffrey Epstein).

Acting rationally is good for one’s self. Acting irrationally is bad for one’s self. To package together these essentially different ways of acting under the term “selfish” or “selfishness” and thus treat them as though they are essentially the same is to mentally mix the logically unmixable and retard one’s ability to think.

“The meaning ascribed in popular usage to the word ‘selfishness’ is not merely wrong,” observes Rand; it represents a package-deal that is “responsible, more than any other single factor, for the arrested moral development of mankind.”

In popular usage, the word “selfishness” is a synonym of evil; the image it conjures is of a murderous brute who tramples over piles of corpses to achieve his own ends, who cares for no living being and pursues nothing but the gratification of the mindless whims of any immediate moment.18

As Rand elaborates in The Virtue of Selfishness, this popular usage makes no sense. Selfishness, meaning “concern with one’s own interests,” logically does not and cannot include mindlessness or disregard for the value or rights of other people. Among other reasons, (a) our reasoning mind is our only means of knowledge and our basic means of living—so failing to use one’s mind is the most selfless thing one can do; and (b) other people can be, and often are, enormously valuable to us—whether by producing material goods or services for trade, or by being business partners, recreational partners, friends, lovers, or (the rarest of all things) rights-protecting politicians.

Using reason and establishing and maintaining life-serving relationships with other people are essential to our survival and happiness. To live and flourish, we must be rational, honest, productive, rights-respecting people—and we must require these same qualities of character in people whom we befriend, partner with, or support.

Every thinking adult knows, on some level, that these principles are true. And when people bear these truths in mind, they can see the glaring differences between people who choose and pursue goals rationally and those who do so irrationally. Given these fundamental differences, it makes zero sense to package together under the same term—“selfishness”—these profoundly different ways of acting.

True selfishness—rational selfishness—is fundamentally different from the mindlessness and self-destructiveness of a parasite or a predator. If we want to think and communicate clearly about what it means to be selfish, we must keep these fundamentally different kinds of actions separate and distinct in our minds. And we should encourage others to do the same. Conceptual clarity is good for everyone who wants to live and flourish.19

###

The foregoing examples of package-dealing show, in pattern, the nature of the fallacy. It consists in combining superficially similar but essentially different things under the same term—thus blurring distinctions that are necessary for clear thinking and clear communication. Be on the lookout for package-deals. You will see them often. And unpacking the illegitimate combinations will improve your mind immensely.

Anti-Concepts: Package-Deals Plus Malice

An anti-concept is a kind of package-deal, in that it combines ideas that logically don’t belong together. But an anti-concept is different from a regular package-deal, in that it is intended to cause conceptual confusion and harm. As Rand defines it, an anti-concept is an unnecessary and rationally unusable term intended to replace and obliterate some legitimate concept(s) in people’s minds.20

The intention can be on the part of those who originated the anti-concept, or on the part of those who use it, or both. Importantly, however, anti-concepts can be, and often are, used innocently by people who are simply confused by the gimmick involved. The following analogy captures the essence of the gimmick.

In Greek mythology, sirens are human-like sea nymphs whose seductive voices lure sailors and their ships into rocks, where they are destroyed. Anti-concepts work in a similar way, but in the sea of concepts—that is, in people’s minds. Anti-concepts lure people to accept and use them; and, when they do, legitimate, life-serving ideas are destroyed in their minds.

An anti-concept involves an alleged meaning—one intended to get you to take the idea seriously and use it—and an actual meaning—one that subverts crucial ideas in your mind if and to the extent that you accept the term as legitimate and attempt to use it. You can think of these as the seductive element and the destructive element. The seductive element involves a connotation that relates either positively or negatively to your rational values, making you feel (vaguely) that the term identifies something important, which deserves your approval or disapproval. If you accept the term as legitimate and try to use it, the destructive element obliterates crucial ideas in your mind—often the very ideas you seek to uphold or protect by using the term.

So, in examining each anti-concept below, we will see four parts:

- A positive or negative connotation;

- An alleged meaning (usually vague), which, combined with the connotation, makes the term or phrase seem legitimate and important;

- An actual meaning, which, when the term is accepted and used, destroys crucial concepts in the minds of its users;

- The legitimate concepts that are obliterated.

The following are some widely used anti-concepts. Once you understand how the gimmick works in these, you’ll be able to spot and deactivate others with relative ease.

Extremism

“Extremism” has a negative connotation: “a bad thing to accept or engage in.” Its alleged meaning is (vaguely) “the immoral act of going to extremes.” These elements get your attention and draw you in by implying, in effect, “You don’t want to be immoral, do you? Then you must oppose this thing!”

But what exactly does “extremism” mean? As Rand observes, on its own, the term has no meaning: “The concept of ‘extreme’ denotes a relation, a measurement, a degree.” Thus, “the first question one has to ask, before using that term, is: a degree—of what?”

To answer: “Of anything!” and to proclaim that any extreme is evil because it is an extreme—to hold the degree of a characteristic, regardless of its nature, as evil—is an absurdity (any garbled Aristotelianism to the contrary notwithstanding). Measurements, as such, have no value-significance—and acquire it only from the nature of that which is being measured.

Are an extreme of health and an extreme of disease equally undesirable? Are extreme intelligence and extreme stupidity—both equally far removed “from the ordinary or average”—equally unworthy? Are extreme honesty and extreme dishonesty equally immoral? Are a man of extreme virtue and a man of extreme depravity equally evil?

The examples of such absurdities can be multiplied indefinitely—particularly in the field of morality where only an extreme (i.e., unbreached, uncompromised) degree of virtue can be properly called a virtue. (What is the moral status of a man of “moderate” integrity?)21

Because no one (rationally) would deny that going to immoral extremes is bad, the actual prescriptive meaning of this term in the minds of those who accept and use it is, “Going to any extreme is bad,” which means, “Consistency to moral principles is bad.”

Observe that consistent advocates of communism or theocracy are called “extremists”—as are consistent advocates of capitalism or rights-protecting government. Consistent advocates of racism are called “extremists”—as are consistent advocates of individualism. Consistent advocates of faith as a means of knowledge are called “extremists”—as are consistent advocates of reason as our only means of knowledge.

Does it make sense to package all these people and positions together under one term—“extremist” or “extremism”—and thus, treat them all as bad? That is what this anti-concept does.22

The purpose of concepts is to mentally integrate our knowledge of the world and of our needs into ideas that keep our minds connected to reality so we can function successfully in reality. The purpose of anti-concepts is, as Rand puts it, “to obliterate certain concepts without public discussion; and, as a means to that end, to make public discussion unintelligible, and to induce the same disintegration in the mind of any man who accepts them, rendering him incapable of clear thinking or rational judgment.”23

Social Justice

“Social justice” has a positive connotation, “a kind of justice.” Its alleged meaning is “the moral imperative of treating people fairly with respect to various social matters.” Together, these elements imply grave importance. They say, in effect, “You want to be just and treat people fairly, don’t you? Then you must be for this thing!”

But is that truly what “social justice” means? If so, how is it distinct from plain justice—which is the virtue of judging people according to the available and relevant facts, and treating them accordingly, as they deserve to be treated? In other words, what is accomplished by adding the prefix “social” to “justice”?

Observe that the plain, non-modified principle of justice already pertains to social matters. It’s about how people living among one another—in a social context—should treat each other in order to be fair. So “social justice” can’t be merely about that. What, then, is the meaning of the phrase?

To answer this, it is helpful to ask: What do advocates of “social justice” seek to accomplish when they embrace and use the phrase? In other words, what purpose does it serve?

On examination, we can see that they use the term to call for political policies that (a) coercively redistribute wealth—forcibly transferring it from people and businesses who produced it to people and groups who didn’t; and (b) force people and businesses to conform to various “social justice” standards. For instance, they demand that the government provide certain groups of people with “free” or “low-cost” housing (“social justice!”)—which means that other people will have to pay for such housing through taxation or inflation (indirect taxation). They demand that the government provide certain groups of people with “free” health care (“social justice!”)—which means that others will have to pay for such health care through taxation or inflation. They demand that businesses, schools, and universities be forced to meet “social justice” litmus tests, such as instituting “affirmative action” policies, using people’s “preferred pronouns,” creating “safe spaces,” granting men paid maternity leave, placing people with correct “intersectionality” on corporate boards, and prohibiting “microaggressions,” “toxic masculinity,” “mansplaining,” and “cultural appropriation” (“social justice!”).

“Social justice” not only calls for coercion against individuals, corporations, schools, and other institutions; it also holds that people in certain “identity groups” can’t think or live successfully without other people being forced to provide them with countless values, pseudo-values, non-values, and absurdities. Which groups of people allegedly can’t think, take care of themselves, or deal with the facts of reality? They are “the poor,” black people, Hispanics, gays, lesbians, people with gender dysphoria, and so on.

That is beyond insulting. It is obscene.

What the individuals in all of those groups need is the same thing all individuals need—and what genuine justice and its corollary, the recognition and protection of individual rights, would provide them if these principles were understood and upheld consistently: freedom to think, to act, to produce, and to trade in accordance with their own rational judgment.

The alleged meaning of “social justice” is “the moral imperative of treating people fairly with respect to various social matters.” Its actual meaning is “the moral imperative of coercively redistributing wealth and forcing individuals and institutions to act against their judgment for the sake of various groups whose individual members allegedly can’t think or live on their own.” In other words, “social justice” is the soft bigotry of low expectations—fused with the hard coercion of a government gun.

The purpose of the anti-concept of “social justice” is to obliterate the concept of actual justice in people’s minds. And, when people accept the phrase as legitimate and try to use it, that is what it does.24

Antiracism

“Antiracism” has a positive connotation: “against racism.” Its alleged meaning is (vaguely) “opposition to all forms of racism, including systemic racism and discriminatory practices that perpetuate racism.” Together, these elements get people’s attention and imply, in effect, “You’re not a racist, are you? And you want to oppose any and all forms of racism, yes? Then you must advocate this position!”

But does “antiracism” truly mean “opposition to racism”?

“Racism,” as Rand observed, “is the lowest, most crudely primitive form of collectivism.”

It is the notion of ascribing moral, social or political significance to a man’s genetic lineage—the notion that a man’s intellectual and characterological traits are produced and transmitted by his internal body chemistry. Which means, in practice, that a man is to be judged, not by his own character and actions, but by the characters and actions of a collective of ancestors.

Racism claims that the content of a man’s mind (not his cognitive apparatus, but its content) is inherited; that a man’s convictions, values and character are determined before he is born, by physical factors beyond his control. This is the caveman’s version of the doctrine of innate ideas—or of inherited knowledge—which has been thoroughly refuted by philosophy and science. Racism is a doctrine of, by and for brutes. It is a barnyard or stock-farm version of collectivism, appropriate to a mentality that differentiates between various breeds of animals, but not between animals and men.25

That is what racism is. And to be against it is, well, to be against it.

Are so-called “antiracists” against it? They are not.

As Ibram X. Kendi—who popularized the term “antiracism”—writes in How to Be an Antiracist, “The opposite of racist isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘anti-racist.’” What does that mean? “Racial discrimination is not inherently racist,” writes Kendi:

The defining question is whether the discrimination is creating equity or inequity. If discrimination is creating equity, then it is antiracist. If discrimination is creating inequity, then it is racist. . . . The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.26

By “discrimination,” Kendi means judging and treating people in accordance with their racial or ethnic group, such as employing “affirmative action programs” to “increase diversity” and “create more equity in our schools, in our colleges, and our workplaces.”27 By “equity” he means “relatively equitable percentages”—that is, percentages roughly equal to each group’s percentage of the general population. These percentages are to be applied to all racial groups in all major areas of life and work, so that all “racial groups are standing on a relatively equal footing.”28 To achieve such “equity,” he advocates an “anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution” to “enshrine” the idea that “racial inequity is evidence of racist policy” and to “establish and permanently fund” a new “Department of Anti-Racism (DOA),” which would be staffed by unelected “formally trained experts on racism.” The DOA would, among other things, “investigate private racist policies when racial inequity surfaces,” and it “would be empowered with disciplinary tools to wield over and against policymakers,” both public and private, who don’t establish and maintain the correct, “antiracist” percentages of racial groups in their organizations.29

In short, “antiracism” is not against racism, but for it. And it is not merely for racism. It is for institutionalized, systemic racism.

“Antiracism” rejects the historically and logically sound idea that the solution to racism is for people and institutions to treat all people as individuals—each with his or her own mind and the ability to think, to choose values, to make decisions, to plan, and to pursue his or her own goals. “Antiracism” rejects Martin Luther King Jr.’s principle that people should be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. And it rejects Frederick Douglass’s view that what black people—and all people—need is to be left alone, left free to think and make their own way in life according to their own choices and values.

“The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us.” Douglass observed. When they ask, “What shall we do with the negro?” he said, “I have had but one answer from the beginning”:

Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength . . . let them fall! I am not for tying or fastening them on the tree in any way, except by nature’s plan, and if they will not stay there, let them fall. And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone! If you see him on his way to school, let him alone—don’t disturb him! If you see him going to the dinner table at a hotel, let him go! If you see him going to the ballot-box, let him alone—don’t disturb him! If you see him going into a work-shop, just let him alone—your interference is doing him a positive injury.30

The morally correct approach to all questions regarding “race” and how people and governments should deal with it is: Recognize the fact that people are individuals—not cogs in a racial collective—and treat them accordingly, as they deserve to be treated. Recognize and uphold their right to live their lives by their own judgment and their own effort.

“Antiracism” says otherwise. It regards people not as individuals but as irrelevant members of an all-important racial group. It calls for forcing everyone to participate in racism, whether or not they want to. It is a philosophy of tribalism—a caveman philosophy—that is intended to destroy the very ideas of “individualism” and “the individual.”31

Polarization

“Polarization” or “polarize” (when used in a social or political context) has a negative connotation: “dangerous ideological division.” Its actual meaning is unclear, writes Rand, but it is alleged to be “something bad—undesirable, socially destructive, evil—something that would split the country into irreconcilable camps and conflicts.”

It is used mainly in political issues and serves as a kind of “argument from intimidation”: it replaces a discussion of the merits (the truth or falsehood) of a given idea by the menacing accusation that such an idea would “polarize” the country—which is supposed to make one’s opponents retreat, protesting that they didn’t mean it. Mean—what? . . .

It is doubtful—even in the midst of today’s intellectual decadence—that one could get away with declaring explicitly: “Let us abolish all debate on fundamental principles!” (though some men have tried it). If, however, one declares; “Don’t let us polarize,” and suggests a vague image of warring camps ready to fight (with no mention of the fight’s object), one has a chance to silence the mentally weary. The use of “polarization” as a pejorative term means: the suppression of fundamental principles. Such is the pattern of the function of anti-concepts.32

Of course, “polarize” has legitimate meaning in physics, chemistry, biology and other fields. So, the word itself is not the problem; the problem arises when it is used as an anti-concept—to replace and obliterate legitimate concepts or ideas in people’s minds, such as the importance of thinking in principles.

Anti-concepts are a plague on rational thinking. They infect the mind and destroy vital ideas. Recognizing and rejecting these malicious gimmicks is essential to mental clarity and to the protection of the values on which human life, liberty, and happiness depend.

What kind of mind-set enables us to detect and eradicate these diseases of the mind?

Rand has an answer to that—and it is not an “open mind.”

Open Mind

“Open mind” has a positive connotation: “willingness to think.” Its alleged meaning is (vaguely) “a mind open to new ideas and willing to judge them impartially.” But the meaning of the phrase is highly ambiguous—and herein lies its danger.

Although “it is usually taken to mean an objective, unbiased approach to ideas,” as Rand observes, “open mind” is also “used as a call for perpetual skepticism, for holding no firm convictions and granting plausibility to anything.” Used this way, the phrase is an “anti-concept.” Rand continues:

A “closed mind” is usually taken to mean the attitude of a man impervious to ideas, arguments, facts and logic, who clings stubbornly to some mixture of unwarranted assumptions, fashionable catch phrases, tribal prejudices—and emotions. But this is not a “closed” mind, it is a passive one. It is a mind that has dispensed with (or never acquired) the practice of thinking or judging, and feels threatened by any request to consider anything.

What objectivity and the study of philosophy require is not an “open mind,” but an active mind—a mind able and eagerly willing to examine ideas, but to examine them critically. An active mind does not grant equal status to truth and falsehood; it does not remain floating forever in a stagnant vacuum of neutrality and uncertainty; by assuming the responsibility of judgment, it reaches firm convictions and holds to them. Since it is able to prove its convictions, an active mind achieves an unassailable certainty in confrontations with assailants—a certainty untainted by spots of blind faith, approximation, evasion and fear.33

Like, “polarize,” “open mind” can be used in a way that is not an anti-concept. Someone could use it to mean what Rand means by “active mind,” and it would be wrong to hold someone in contempt for using it that way. But when someone uses “open mind” to argue that “no one can really know anything, so we can accept any and all ideas as equally valid or invalid” or to avoid the responsibility of thinking and drawing conclusions based on evidence and logic, he is using it as an anti-concept. And, when he does, it destroys vital ideas in his mind and in the minds of others who accept such usage.

###

There are many more anti-concepts (consumerism, marginalization, cultural appropriation, Islamophobia, international law, isolationism, etc.), but the samples above provide an indication of how they work and how widespread they are. Be on the lookout for them. Identify the gimmick at play. And avoid using them except to point out why they shouldn’t be used.

Rand’s Razor

In the light of the foregoing examples of package-deals and anti-concepts, it’s helpful to see these fallacies as violations of Rand’s Razor: “Concepts are not to be multiplied beyond necessity . . . nor are they to be integrated in disregard of necessity.”34

If we multiply concepts beyond necessity—that is, if we create “concepts” that have no actual referents in reality—we litter our minds (and those of others) with useless words or, worse, anti-concepts, which destroy our capacity to think or communicate clearly about important matters. If we integrate concepts in disregard of necessity—that is, in disregard of our need to make crucial distinctions among things based on fundamental differences—we create package-deals, which retard our ability to think or communicate clearly about important matters.

Whether or not a new concept should be formed (multiplied), and whether or not existing concepts should be integrated, depends on the requirements of human cognition—namely, our conceptual needs and the purpose of our cognitive faculty, which is to identify, integrate, and differentiate things in reality based on factual similarities and differences.

If we want to keep our minds connected to reality so that when we think and talk we know what we are thinking and talking about, we need to mentally combine essentially similar things and mentally separate essentially different things. Rand’s Razor reminds us to do so. (For more on this principle, read Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology.)

The Fallacy of the Frozen Abstraction

The fallacy of freezing an abstraction consists in making a false equation by substituting a particular conceptual concrete for the wider abstract class to which it belongs.35 Like a package-deal, it involves integrating concepts in disregard of the need for crucial distinctions.

Rand’s seminal example of this fallacy is the equating of “morality” with “altruism” by substituting a particular morality (the morality of self-sacrifice) for the whole, general class “morality.” Although altruism is a kind of morality, it is not the only kind of morality; it is not morality as such. The concept of “morality” is a broad category subsuming several kinds or codes of morality—altruism, egoism, hedonism, utilitarianism, and others. To substitute the concept of “altruism” for the concept of “morality” is to exclude from the broad category of “morality” all of the other moral codes that are properly included under it. The question of which (if any) code is demonstrably true is a separate matter—and an extremely important one. Yet, when people equate morality with altruism, this question is removed from consideration.

Just as we don’t treat “math” as the equivalent of “algebra,” or “medicine” as the equivalent of “aspirin,” or “religion” as the equivalent of “Christianity”—so too we shouldn’t treat “morality” as the equivalent of “altruism.”

Likewise, in pattern, for other frozen abstractions, which include the following false equations.

Morality = Religious Morality

This equation substitutes an alleged God’s commandments or religious dogma for the entire field of morality and thus excludes from consideration all secular, non-religious moral codes. Acceptance of this notion blinds people to the possibility of a natural, this-worldly moral code.

Causality = Mechanistic Causality

This equation substitutes mechanistic causality for causality as such and thus excludes from consideration other forms of causality, such as that of consciousness (i.e., the ways in which consciousness causes action) and that of volition (a person’s choice to think or not to think). Among other problems, acceptance of this frozen abstraction blinds people to the existence and nature of free will.

Philosophic Truth = Objectivism

This equation substitutes the philosophy of Objectivism for philosophic truth as such, treating all philosophic truths as parts of Rand’s philosophy. In addition to absurdly crediting Rand for all philosophic discoveries (past, present, and future) and thus denying that anyone else has ever discovered a philosophic truth, acceptance of this false equation disintegrates Objectivism in people’s minds by leaving its identity “open” to change anytime anyone claims to have discovered a new philosophic truth. (See my debate with Stephen Hicks about this here.)

Logic = Deduction

This equation substitutes the process of deduction (the application of truths and generalizations) for the entire field of logic, thus excluding the processes of induction (the inference of generalizations or principles), reduction (the identification of the chain of ideas that connect an idea to perceptual reality), and integration (the process of uniting elements into an inseparable whole). Among other problems, acceptance of this frozen abstraction precludes people from understanding how valid generalizations and principles are formed, how to ground ideas in perceptual reality, and how to check potential items of knowledge for unity with their broad network of observation-based knowledge.

Claims to Certainty = Dogmatism

This equation substitutes unfounded claims to certainty for any and all claims to certainty, thus excluding the possibility of evidence-based, logically warranted, conceptually integrated certainty.

Government = Tyranny

This equation treats all forms of government as tyrannical and thus excludes the possibility of properly limited, rights-protecting government, the kind that uses physical force only in retaliation and only against those who initiate its use.

###

Frozen abstractions retard people’s thinking and cause widespread confusion on important issues. Look for them. Defrost them. And call things precisely what they are.

Floating Abstractions and Stolen Concepts

Conceptual knowledge is hierarchical. Higher-level concepts, such as mammal, animal, mile, and tyranny, presuppose and depend on lower-level concepts, all the way down to first-level concepts, whose referents are at the perceptual level, such as dog, bird, inch, and force (e.g., a punch in the face). In order to know what a mammal is, you must first understand a chain of more basic concepts, including fertilization, reproduction, animal, and various kinds of animals (e.g., cats, dogs, birds, fish). Without this more basic knowledge, the concept of mammal wouldn’t and couldn’t have meaning in your mind.

This principle of hierarchy applies to all conceptual knowledge. Higher-level (more abstract) concepts can be understood and have meaning in someone’s mind only to the extent that he grasps the lower-level (more basic) concepts that give rise to them. And there are essentially two ways people can violate this principle: via floating abstractions and via stolen concepts.

Floating Abstractions

When someone uses a word or phrase that is not supported in his mind by a structure of more basic ideas that are ultimately grounded in perceptual facts, he is using a floating abstraction—an abstraction disconnected from reality in his mind, disconnected from the things the idea refers to, disconnected from the facts that give it meaning.

For example:

“Everyone has a right to a living wage.” If someone uses the word “right” this way, he doesn’t know what a right is. He doesn’t know what the concept means, what it refers to in reality. He doesn’t know the facts that give rise to our need for the concept. (Or, if he does, he is committing a more grievous fallacy; see concept-stealing below.)

A right is a moral prerogative to act in accordance with one’s own judgment, and it is based on the fact that in order for a human being (such as a business owner) to live fully as a human being, he must be fully free to act in accordance with the faculty that makes him human: his reasoning mind. The notion that someone could have a “right” to a “living wage” implies that a business owner could legitimately be forced to pay an employee a wage that the business owner thinks is too high. This implication contradicts the very meaning of the concept of right. And when someone uses the word “right” this way—disconnected from its actual meaning and the facts that give rise to it—he commits the fallacy of the floating abstraction (or worse, the stolen concept, per below).

“Thou shalt honor thy father and thy mother.” If someone thinks or says this, he doesn’t know what “honor” means.

To honor someone means to regard him with great respect. If someone holds as an unconditional rule or categorical imperative that a person should honor or greatly respect his parents, he doesn’t understand the facts that give rise to our need for concepts such as honor and respect.

We need such concepts because (a) people have free will, which means they can choose to act in extremely rational, life-promoting ways, or in extremely irrational, life-harming ways, or anywhere in between—and (b) we need to judge people in accordance with the available and relevant facts regarding their nature and chosen behavior. Some people deserve respect and honor, because they have earned it. Others do not, because they have not.

Whether someone should honor or respect his father or mother depends on whether he or she deserves honor or respect. It would be monstrous to hold that someone should honor a parent who psychologically or physically abused him.

To hold or claim that someone should honor his parents no matter what is to hold or use the concept as a floating abstraction (or worse, a stolen concept, per below).

“America is a democracy.” If someone thinks or says such a thing, he doesn’t know what “democracy” means (see “democracy” as a package-deal above). The term is a floating abstraction in his mind.

“From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” If someone chants such nonsense, he has no idea what “free” means. The term is a floating abstraction in his mind.

###

Floating abstractions abound. Be on the lookout for them in your own mind and in the claims of others. Work to keep your concepts connected to reality, and help those you care about to do so, too. Everyone who wants to think clearly, live fully, and defend liberty will benefit from the effort.

Concept-Stealing

Now, if someone goes beyond merely using a concept that is disconnected from reality and uses a concept while denying or ignoring more basic, lower-level concepts on which it logically depends, he is committing the fallacy of concept-stealing.

Here, as with floating abstractions, the operative principle is the hierarchical nature of conceptual knowledge. Higher-level, more abstract knowledge is built on lower-level, more basic knowledge, all the way down to sensory perception, our direct cognitive contact with reality. Concept-stealing consists in using a higher-level concept while denying or ignoring a lower-level concept(s) on which it depends for its meaning.36 To use a concept in this way is to tear it away from the base that gives rise to it, the hierarchy to which it belongs, the foundation that grounds it in reality.

Examples:

“Thinking” or “Thoughts” Apart from a Thinker

When someone claims that there is no thinker of thoughts, that thinking just happens and does not involve a thinker, he steals the concept of “thinking.”

For instance, when Sam Harris argues that “the self is an illusion,” that it’s false to hold that there’s “an ego, an I, a thinker of thoughts in addition to the thoughts,” he steals the concept of thoughts. Where do thoughts come from if not from a thinker? What generates them? Harris answers: “If you look closely at thoughts themselves, you will notice that they continually arise and pass away. If you look for the thinker of these thoughts, you will not find one. And the sense that you have—‘What the hell is Harris talking about? I’m the thinker!’—is just another thought, arising in consciousness.”37

In making this claim, Harris acknowledges that thinking exists but denies the existence of the thing that thinks: the thinker (i.e., the self). The fallacious nature of such a claim is evident simply on the grammatical level: Verbs presuppose nouns. Actions are actions of entities or agents. Just as for sprinting to occur, there must be a sprinter who sprints; so, too, for thinking to occur, there must be a thinker who thinks.

“Consciousness” or “Awareness” Apart from Existence

When someone argues that we can first be certain of consciousness or awareness but not of external existence or external reality, as Rene Descartes did, he steals the concept of “consciousness” or “awareness.”

Consciousness or awareness presupposes something to be conscious or aware of. If I say, “I’m aware,” and you ask, “Aware of what?” and I reply, “Of nothing but my awareness,” you would justifiably retort, “That makes no sense.” And you’d be right. As Rand put it:

If nothing [apart from consciousness] exists, there can be no consciousness: a consciousness with nothing to be conscious of is a contradiction in terms. A consciousness conscious of nothing but itself is a contradiction in terms: before it could identify itself as consciousness, it had to be conscious of something.38

Of course, we can be and are conscious of our consciousness (or aware of our awareness)—but only because we are already conscious of things in external reality. A baby is not born, eyes closed, thinking “Lookie there in my head, I’m conscious!” Rather, when he opens his eyes he sees things, when he moves his limbs he touches things, and so on. This is how he becomes aware of the world. Only much later is he able to introspect and become aware of his consciousness as another thing in reality.

Consciousness presupposes and depends on external existence. Thus, to use the concept of consciousness (or awareness) while denying, ignoring, or doubting the existence of an external reality is to tear the concept away from the foundation that gives it meaning.

Rand called this particular stolen concept “the prior certainty of consciousness,” and she elaborated on the error and its devastating philosophic and historic consequences in her book For the New Intellectual, which I highly recommend.

“Fallibility” or “Error” Apart from Knowledge or Certainty

When someone claims or implies that, because we are fallible (or capable of error), we can never know whether we possess knowledge or certainty (as skeptics and pragmatists do), he steals the concept of “fallible” (or “error”).

This is evident on multiple counts: To say that people are fallible is to assert an item of knowledge. To know that people are fallible, one must first know that people have erred. And to know that, one must possess knowledge of the truths against which their errors were shown to be errors.

As Leonard Peikoff succinctly puts it: “Fallibility does not make knowledge impossible. Knowledge is what makes possible the discovery of fallibility.”39

“Value” or “Morality” Apart from Life

When someone discusses value or morality (a code of values) yet denies or ignores the factual standard of value, which is life (i.e., the requirements of the life of the particular organism in question), he thereby tears the concept of “value” away from the foundation that connects it to reality and gives it objective meaning. He steals the concept. As Rand put it:

Metaphysically, life is the only phenomenon that is an end in itself: a value gained and kept by a constant process of action. Epistemologically, the concept of “value” is genetically dependent upon and derived from the antecedent concept of “life.” To speak of “value” as apart from “life” is worse than a contradiction in terms. “It is only the concept of ‘Life’ that makes the concept of ‘Value’ possible.”40

The reason that to speak of value as apart from life is worse than a contradiction in terms is that to do so is to tear the concept of value away from the foundation on which it depends and in relation to which it has meaning. Ripped away from life, value has no grounding in reality; it is severed from its factual base; it is a stolen concept.

(For more on how values and morality are made possible and necessary by life, see Rand’s The Virtue of Selfishness and my Loving Life.)

“Experiment” or “True” Apart from Free Will

When someone claims that an experiment has shown that determinism is true—that all human action is antecedently necessitated by forces beyond our control—he steals the concepts of “experiment” and “true.”

An experiment presupposes and depends on the fact of choice: To perform an experiment, the experimenter must choose the variables he will control, he must choose the factors he will isolate, he must choose the data he will include and exclude. If his actions were determined by forces beyond his control, then his alleged experiment would not be an experiment; it would be a series of predetermined actions over which he had no control. And his alleged conclusion would not be a conclusion, much less a true conclusion; rather, it would be a necessary outcome of the predetermined actions that caused it. It would be no more (or less) true or valid or scientific or controlled or sound than any other result of any other antecedently necessitated actions performed by any other alleged experimenter—including one whose “experiment” showed that human beings do possess free will.

If determinism were true, all cognitive activity, all arguments, and all conclusions—including those of people claiming free will is true and those of people claiming determinism is true—would be determined; thus, none would have any greater cognitive status or truth value than any other. Indeed, none would have any greater truth value than a dog’s bark, a snake’s slither, or a river’s flow.

(For more on the nature of free will, see “Free Will and Flourishing.”)

“Invalid” Apart from the Validity of the Senses

When someone claims the senses are invalid, he steals the concept of “invalid.” (Invalid, in this context, means “incapable of delivering knowledge of reality.”)

To begin with, the claim that a sensory apparatus, such as eyes, ears, or skin, is incapable of delivering knowledge of reality presupposes that one possesses some knowledge of the apparatus in question. For instance, if I say, “Eyes can’t provide data about reality,” and you reply, “What are eyes?”—what’s my next move?

Further, all knowledge we have of everything we think and talk about began with and is rooted in sensory perception. We can and sometimes do make up fantasy things, such as unicorns, based on real things we know about, such as horses and horns. But to make up such fantasy things, we must first have knowledge of real things.

And we can and sometimes do misinterpret data provided by the senses. But this is not a failure of the senses. Rather, it’s a powerful indication of their validity.

For instance, a straight stick protruding from a glass of water appears bent beneath the surface of the water. Is this a failure of our sense of sight? It is not. Our eyes are perceiving a wide range of data, which, to be understood, must be rationally interpreted. This data includes effects of the fact that light travels at a different speed through water than through air. These differences in speed, which are facts of reality, cause light passing through water and light passing through air to have correspondingly different effects on our retinas. Our sight is not omitting these facts and data but including them. The job of our eyes (and our other senses) is to deliver all the raw data they are capable of delivering. The job of our reasoning mind is to interpret such data correctly. This same kind of explanation applies to all alleged failures of the senses. (For more on this, see “The Senses as Necessarily Valid,” in chapter 2 of Peikoff’s Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand.)

When our sensory apparatuses and our reasoning faculty work together, we can come to understand reality ever more deeply and fruitfully, which is why human beings have come to know so much and achieve so much (look around). Don’t let people’s use of stolen concepts fool you into doubting the efficacy of your senses. Your senses perceive reality. There is nothing else to perceive.

“Why” Apart from Something

When someone asks “Why is there something rather than nothing?” (as in, “Why is there existence rather than nonexistence?”) he steals the concept of “why.”

The purpose of the concept of why is to ask for or to identify the cause or purpose of some particular thing, or organization of things, or relationship among things. In the question “Why is his car in the driveway?” for instance, why refers to the cause of or reason for the car being there. In the statement “There is no evidence for the existence of God, that’s why I don’t believe in him,” why refers to the cause of or reason for the speaker’s disbelief. In the question “Why did you move to New York City?” why refers to the purpose or motive of your move. And so on. In all such cases, the existence of certain things is a given. It’s a given that the car, the driveway, someone’s disbelief, your purpose, your state of residence, and the like exist. In all such cases, the concept of “why” has referents. It refers to things. It means something.

But to ask “Why is there something rather than nothing?” is (a) to assume that there once was nothing and, then, for some reason, that alleged nothing caused something to come into existence—and (b) to ask why the supposed nothing did this. To use “why” this way is to tear the concept away from the facts that give rise to our need for it, the context in which it has meaning. That context is existence, this world in which we live, a world of things that have identities and that act in accordance with their identities. Apart from that context, why has no meaning.

Rand called this particular variant of concept-stealing the “Reification of the Zero.” As she explained:

It consists of regarding “nothing” as a thing, as a special, different kind of existent. (For example, see Existentialism.) This fallacy breeds such symptoms as the notion that presence and absence, or being and non-being, are metaphysical forces of equal power, and that being is the absence of non-being. E.g., “Nothingness is prior to being.” (Sartre)—“Human finitude is the presence of the not in the being of man.” (William Barrett)—“Nothing is more real than nothing.” (Samuel Beckett)—”Das Nichts nichtet” or “Nothing noughts.” (Heidegger). Consciousness, then, is not a stuff, but a negation. The subject is not a thing, but a non-thing. The subject carves its own world out of Being by means of negative determinations. Sartre describes consciousness as a ‘noughting nought’ (néant néantisant). It is a form of being other than its own: a mode ‘which has yet to be what it is, that is to say, which is what it is, that is to say, which is what it is not and which is not what it is.’” (Hector Hawton, The Feast of Unreason, London: Watts & Co., 1952, p. 162.)41

###

Stolen concepts are rampant in philosophic discussions. And they not only cause confusion; they also make way for much mischief and lead people to waste ungodly amounts of time pondering and debating things that don’t exist, don’t make sense, or don’t matter. Be on the lookout for them.

When thinking about philosophic matters or entering into philosophic discussions, ask yourself what the key concepts involved mean, what ideas they depend on, what facts connect them to reality. Check to ensure that you’re not using or accepting ideas while denying or ignoring more basic ideas on which they depend.

Keeping your thinking connected to reality is essential to success in reality. And that’s the only kind of success there can be.

Note: This is a living document, to which I’ll add material over time. Suggestions for improvement or addition are welcome. —Craig

Endnotes

- Some of the material in this document is drawn from my article “Navigating Today’s Seductive and Destructive Language (A Study of Package-Deals and Anti-Concepts),” in The Objective Standard 18, no. 2. ↩︎

- Ayn Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 2nd ed., edited by Harry Binswanger and Leonard Peikoff (New York: Penguin, 1990), 13. ↩︎

- See Ayn Rand, “How to Read (and Not to Write),” in The Ayn Rand Letter 1, no. 26. ↩︎

- For more on this package-deal, see my article “The Equality Equivocation,” The Objective Standard 9, no. 4. ↩︎

- Ayn Rand, “America’s Persecuted Minority: Big Business,” in Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal (New York: Signet, 1967), 46. ↩︎

- For more on this, see Rand, “America’s Persecuted Minority,” and Michael Dahlen, “The Assault on Corporations,” in The Objective Standard 15, no. 3. ↩︎

- For more on the true nature of rights, see Rand’s essays “Man’s Rights,” “Collectivized ‘Rights,’” and “”The Nature of Government” in The Virtue of Selfishness (New York: Signet, 1964); see also my essay “Ayn Rand’s Theory of Rights: The Moral Foundation of a Free Society” in Rational Egoism: The Morality for Human Flourishing (Richmond: Glen Allen Press, 2019) or in The Objective Standard 6, no. 3. ↩︎

- For more on the true nature of capitalism, see Rand, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal; Michael Dahlen, “Corporations and Political Corruption: The Curse of Cronyism and How to End It,” The Objective Standard 15, no. 4; and my essay “Capitalism and the Moral High Ground,” The Objective Standard 3, no. 4. For additional clarity on the related matter of how package-dealing muddies the waters in regard to the left-right political spectrum, see my articles “Political ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ Properly Defined,” The Objective Standard 7, no. 3, and “The Vital Function of the Political Spectrum,” The Objective Standard 12, no. 2. ↩︎

- For more on rational secularism, see Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It and The Virtue of Selfishness; and my Loving Life: The Morality of Self-Interest and the Facts That Support It (Richmond: Glen Allen Press, 2002) and Rational Egoism. ↩︎

- For more on this, see my essays “Religion vs. Subjectivism: Why Neither Will Do,” The Objective Standard 4, no. 1; and “Religion Is Super Subjectivism,” The Objective Standard 12, no. 2. ↩︎

- Rand, “How Does One Lead a Rational Life in an Irrational Society?” in Virtue of Selfishness, 82–83. ↩︎

- For more on this package-deal, see my article “The Ground Zero Mosque, the Spread of Islam, and How America Should Deal with Such Efforts,” The Objective Standard 5, no. 3; my “Reply to a Letter about Toleration,” The Objective Standard 6, no. 1; and my video “Islam, Tolerance, and Rights” on YouTube. ↩︎

- Rand, “The Ethics of Emergencies,” in Virtue of Selfishness, 51. ↩︎

- For elaboration on this package-deal, see my video “Why ‘Sacrifice’ Means Loss, Not Gain,” on YouTube. ↩︎

- Thomas Nagel, The Possibility of Altruism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978), 79, emphasis added. ↩︎

- Peter Singer, A Darwinian Left (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 56, emphasis added. ↩︎

- For more on the nature of altruism and how it stands in stark contrast to the morality of self-interest, see Rand’s Virtue of Selfishness, and my Loving Life and Rational Egoism. ↩︎

- Rand, introduction, Virtue of Selfishness, vii. ↩︎

- For more on the true nature of selfishness, see Rand, Virtue of Selfishness; my Loving Life and Rational Egoism; and my video “Why Use the Term Selfishness?” on YouTube. ↩︎

- See Rand, “Credibility and Polarization,” in The Ayn Rand Letter; “‘Extremism,’ or The Art of Smearing” and “The Obliteration of Capitalism,” in Capitalism; and “Causality Versus ‘Duty,’” in Philosophy. The definition here is a combination of her several definitions. ↩︎

- Rand, “Extremism,” 197. ↩︎

- For elaboration on “extremism,” including how it and related anti-concepts are used to smear capitalism and its advocates, see Rand, “‘Extremism,’” in Capitalism. ↩︎

- Rand, “Extremism,” 177. ↩︎

- For more on this anti-concept, see my video “‘Social Justice’ Is an Assault on Justice” on YouTube. ↩︎

- Rand, “Racism,” in Virtue of Selfishness, 147. ↩︎

- Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (New York One World, 2019), Kindle edition loc. 433. ↩︎

- Quoted in Grace Baek, “Affirmative Action and the Diversity Dilemma,” CBSN Originals, April 15, 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/affirmative-action-and-the-diversity-dilemma/. ↩︎

- Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist, Kindle edition, loc. 406–409. ↩︎

- Ibram X. Kendi, “Pass an Anti-Racist Constitutional Amendment,” Politico Magazine, 2019, https://www.politico.com/interactives/2019/how-to-fix-politics-in-america/inequality/pass-an-anti-racist-constitutional-amendment/. ↩︎

- Frederick Douglass, “What the Black Man Wants,” a speech at the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in Boston, April 1865, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/africam/afspfdat.html. ↩︎

- For more on the rational assessment of racism, see Ayn Rand’s essay “Racism,” in Virtue of Selfishness; and Tim White, “To Black Lives Matter, No Lives Matter,” The Objective Standard 15, no. 3. ↩︎

- Rand, “Credibility and Polarization.” ↩︎

- Rand, “Philosophical Detection,” in Philosophy, 21. ↩︎

- Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 2nd ed., edited by Harry Binswanger and Leonard Peikoff (New York: Penguin, 1990), 72. Rand identified two philosophic razors. The other one is that every philosopher should state his irreducible primaries (or axioms). If this were required “before being permitted to utter a proposition,” she mused, “boy would the field shrink” (251). ↩︎

- See Rand, “Collectivized Ethics,” in The Virtue of Selfishness, 94. ↩︎

- For more on concept stealing, see Rand, “This is John Galt Speaking,” in For the New Intellectual (New York: Signet, 1961), 154; Nathaniel Branden, “The Stolen Concept,” in The Objectivist Newsletter 2, no. 1: 2; and Leonard Peikoff, Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand (New York: Meridian, 1993), 136–37. ↩︎

- Sam Harris, “The Self is an Illusion,” Big Think, September 16, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fajfkO_X0l0; Gary Gutting, “Sam Harris’s Vanishing Self,” New York Times, September 7, 2014, https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/09/07/sam-harriss-vanishing-self/. ↩︎

- For the New Intellectual, 124. ↩︎

- Peikoff, “Maybe You’re Wrong,” in Why Act on Principle? (Santa Ana: ARI Press, 2024), 23. ↩︎

- Rand, “The Objectivist Ethics,” p. 18. ↩︎

- Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 60–61. ↩︎

Alex O’Connor’s Red-Herring Thought Experiment vs. Facts that Support Morality